How Microfluidics Are Changing Synthetic Biology

What is Synthetic Biology?

The great potential of synthetic biology first caught my attention during my undergraduate years as a structural biologist. As a researcher studying protein design, it was exciting to see how the understanding of protein functions could be put to use. For the uninitiated, synthetic biology is the field of biology focused on designing and building biological devices, whether from living cells or from cellular components such as enzymes, proteins, and DNA. Many devices consist of relatively simple alterations to a cell that provide some useful function. One real-world example currently in use as a cancer therapeutic is a CAR-T cell. These are immune cells collected from a patient and altered to produce a receptor on their surface that allows them to recognize and engage cancerous cells. While decades of research were required to achieve this, it is now a reality that is expanding in the medical community. Many other examples exist, and the field is rapidly growing.

However, not all synthetic biology is contained within a cell. As researchers explore the life of a cell, its systems and machinery can be isolated and applied to tasks outside of supporting cellular life. PCR tests used to detect the Covid virus are one example. In PCR, the DNA polymerase, responsible for copying the DNA of a cell before cell division, is removed from its cellular environment and used in the lab. When DNA and some other key items are mixed with it, it does what it does best and begins copying DNA. In the case of Covid testing, it amplifies a stretch of DNA that identifies Covid infection. For our purposes, what’s interesting is that it works outside the cell, in a lab setting, and is easily scalable, as demonstrated during the pandemic. DNA polymerase is not the only cellular component to function outside of the cell, and every day, more and more cellular machinery is being adopted into our daily lives by researchers and industry.

Understanding Protein Environments

Among the many cellular components that sustain life at the microscopic scale, proteins stand out as extraordinarily interesting, both for their function in the cell and for their ability to be adapted for uses outside of it. The more than ninety thousand proteins known as of this writing may be categorized in many ways, and one aspect researchers use is whether they are found in the lipid membrane of cells or floating in the cytoplasm. Generally, soluble proteins, which are found in the cytoplasm, are easier to work with since they do not require a lipid membrane for isolation and may function in a liquid solution with minimal adjustments. However, lipid membrane-bound proteins, referred to as membrane proteins, carry out many important tasks in the cell and are a relatively untapped resource for applications outside of it.

Learn More About Proteins

Membrane-Associated Proteins and the Power of the Lipid Barrier

One of the most exciting features of working with proteins is exploring their function when paired with a membrane. This partnership opens up a whole new world of possibilities. Some proteins, like proteorhodopsin and ATP synthase, act as microscopic machines that help push protons across the membrane, building up a proton gradient. That gradient becomes a cellular battery, storing energy that other proteins can tap into. One example is the flagellar motor: a protein complex that uses this proton battery to spin a tail-like flagellum at an RPM similar to a jet engine, propelling the entire cell forward.

In my own work, I’ve become especially interested in the utility that membranes offer. In nature, a huge portion of the proteins in a cell, sometimes more than half, are embedded in or attached to the membrane. These proteins include the motors mentioned above, chemical receptors, pores, transporters, and adhesins, all working together to let the cell sense and respond to its environment.

When I first started designing sensors to detect small molecules, I looked to these natural receptors for inspiration. They’re specific, robust, and already optimized by evolution to work in complex environments. My goal was to build sensors that could be arranged in precise patterns, with control over how many of each were present and where they ended up, ideally attached to a surface where they could stay put. My aim was to mimic biofilms: communities of microbes which may be arranged in particular patterns and are known for their ability to accumulate and persist in challenging environments.

That’s where giant unilamellar vesicles, or GUVs, come in. GUVs are synthetic lipid structures that closely mimic the membranes of real cells, though without the many proteins and other features found in living cell membranes. They provide the ability to encapsulate solutions and allow researchers to study protein interactions within a simplified lipid system. Recently, researchers aiming to build cell-like systems from the ground up have used GUVs as a framework to encapsulate simple transcription and translation mixtures. These systems provide some of the functionality of living cells while avoiding much of their complexity.

My goal has been to design a GUV-based biosensor that mimics key features of natural cells, especially their ability to sense and respond to their environment. To do this, I’ve been working to decorate GUVs with chemical receptors and adhesins, proteins that help cells stick to surfaces or to one another. Inside each vesicle, I include a solution that can produce a measurable response when these receptors are activated. The idea is to create a bio-inspired sensor that captures the advantages of natural cells, without the risks associated with releasing engineered living organisms into the environment. By measuring outputs, such as fluorescence, a color change, or another signal, the sensor would be able to report changes in its environment. The result is a sensor with the specificity, sensitivity, and resolution of a bacterial cell but safe to deploy in sensitive ecological environments.

Making GUVs: A Few Popular Methods

There are several ways to make GUVs, each with its pros and cons. Here are three methods researchers often use:

Thin Film Hydration and Extrusion

This classic approach starts by drying lipids onto a surface to form a thin film. You then add your internal solution and agitate the mixture, encouraging vesicles to form as the lipids rehydrate. The result is usually a mix of sizes, so researchers often pass the vesicles through a filter with tiny pores (using a syringe extruder) to standardize their size. The vesicles get sheared and re-sealed as they pass through, becoming more uniform with each round.

This method is reliable and produces ideal GUVs with uniform size in significant concentrations. However, the agitation may cause problems when working with proteins due to their tendency to degrade under shear forces. Also, a larger volume of internal solution must be used, which can be costly.

Inverted Emulsion

In the inverted emulsion method, GUVs are formed by taking advantage of how lipids behave at oil–water boundaries. First, the lipids are fully dissolved in an oil solution. Then, a small amount of water-based solution, destined to become the interior of the GUV, is vigorously mixed into the lipid-containing oil. This creates an emulsion (shown in orange in the video below). The charged lipid headgroups in the oil are attracted to the water droplets and form a single lipid layer surrounding each droplet, the first step of lipid bilayer assembly.

Next, this emulsion is carefully layered on top of another water-based solution, which will become the external environment of the final GUVs (shown in blue below). At this point, the system consists of two layers: the oil-emulsion floating on top of the aqueous phase below.

To help the droplets move through the oil and into the water phase, the entire setup is centrifuged. The force of centrifugation pushes the droplets downward, creating a pellet at the bottom of the tube, as shown in the video. As each droplet crosses the oil–water interface, the lipids on its surface reorganize to form a complete lipid bilayer, one layer facing inward and one facing outward, mimicking the structure of a natural cell membrane. In doing so, each droplet becomes encapsulated in a bilayer, forming a GUV.

This method allows researchers to control both the contents of the vesicle and the surrounding environment, which is especially useful when building synthetic systems meant to mimic or interface with biological cells.

While this method is beneficial due to its simplicity, results tend to be inconsistent. Yields can be low, vesicle sizes are non-uniform, and clumping is commonly encountered.

Animation created in Blender by the author (© 2025).

Microfluidic Production

Microfluidics is the control of fluids at the micron scale. This technique uses sub-millimeter liquid channels to build GUVs with high precision. These chips usually have three inlets (one each for the internal solution, lipid-in-oil, and external solution) and one outlet. As the fluids flow together, they assemble vesicles one by one. Because everything happens at such small volumes, this method minimizes waste and allows for fine control, which is especially helpful when experimenting with new designs or expensive reagents.

As shown in the video below, the inner solution (represented by a circular DNA plasmid) travels through the channel and encounters a lipid-in-oil solution (shown in red) at the first junction. As the inner solution is pushed into the lipid and oil, the lipids begin forming a single layer across its surface. Applied pressure then pinches off the droplet, creating a unit surrounded by a lipid monolayer.

The droplet continues along the channel and next encounters the outer aqueous solution, the intended external environment for the GUV. As the droplet is forced across the interface, a second lipid layer forms, with its charged headgroups facing outward. Again, pressure pinches off the droplet and sends it along the channel toward the outlet. As it moves along, the remaining oil is separated from the lipids, either by surfactants or mechanical design, resulting in a fully formed lipid bilayer encapsulating the inner solution.

This method provides precise control over GUV size, uses far smaller volumes than thin film hydration, and is gentler on proteins. It also enables continuous production. However, the setup is relatively costly compared to other methods, and skill is required to operate the system and maintain balanced pressures at each inlet.

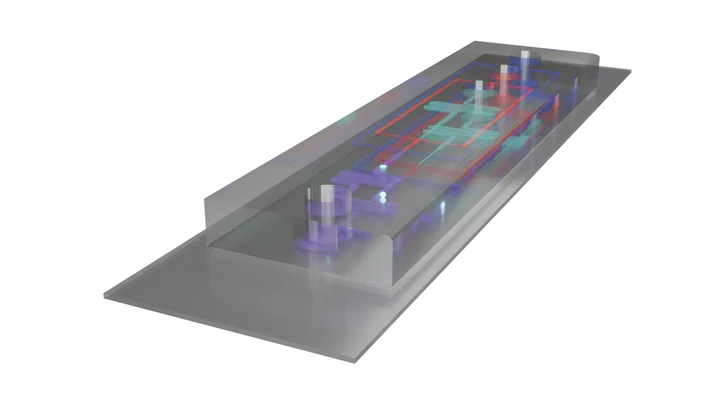

Below, you can explore the microfluidic device in 3D and watch the video showing how the lipids assemble.

Model created in Fusion360, redered in Blender, and displayed in model-viewer by the author (© 2025).

Animation created in Blender by the author (© 2025).

How Will Microfluidics Change the Field?

As microfluidic production of GUVs continues to mature and see wider adoption, researchers will gain the ability to produce GUVs at much greater scales. This shift opens the door to applications that extend beyond basic research. With microfluidics, it becomes possible to manufacture GUVs for a wide range of uses, from simple lipid-based systems to fully functional synthetic cells, as imagined by synthetic biologists.

As production methods become more standardized and refined, continuous and parallel manufacturing will be within reach. This could allow GUVs to compete with existing cell-based platforms, such as bacteria and yeast, in areas like biomanufacturing. Looking further ahead, GUV-based systems may even serve as safer, more controllable alternatives to engineered immune cells in therapeutic applications.